A soulful visit: experiencing Noh, Zen and Tea in Kanazawa

Sophie Richard wanders around Japan

Words by Sophie Richard

A soulful visit: experiencing Noh, Zen and Tea in Kanazawa

Kanazawa was ruled during the Edo period (1603-1866) by the Maeda clan, its successive daimyos, or feudal lords, actively invited artists and craftsmen to settle there and work for them. The city’s flourishing economy and culture during the period made it one of the most creative at the time and this legacy continues today. It is indeed notable in Kanazawa’s many fine museums, which present a varied and rich tapestry. The museums give visitors the opportunity to delve into Japanese culture, not only by looking but also by experiencing first-hand certain aspects of it. On a recent visit to Kanazawa, I relished on three pillars of Japanese traditional culture, namely Noh theatre, Zen and the tea ceremony and also reflected on how they are linked.

Noh was historically very popular in Kanazawa, thanks to the Maedas’ patronage for this traditional dramatic art which was particularly favoured by the samurai class. It was for the clan an illustration of its power, taste and sophistication. At the Kanazawa Noh Museum, in discussion with the curator, I learned that the Maeda family attended Noh with its entourage while also encouraging common people to enjoy performances and to participate in them. There were therefore not only professional actors but also tradesmen and craftspeople taking to the stage. The deep-rooted taste for this form of entertainment meant that Noh continued to strive in Kanazawa even after the Meiji Restoration (1868) when it saw a strong decline in other parts of Japan.

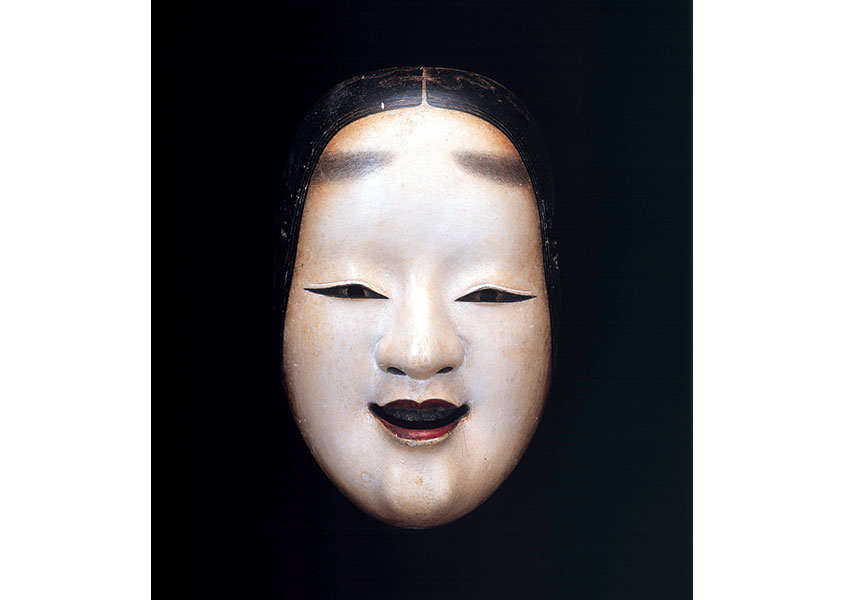

The museum presents artefacts that come mostly from the collection of one man who was passionate about Noh. There are gorgeous costumes dating from the late Edo period, when Noh was arguably at its peak, including colourful robes that reveal sumptuous brocades heavy with gold. Noh costumes displayed the most sophisticated techniques in textile design at the time. As there are almost no props on a Noh stage, costumes can provide clues about the story; for example, if the action unfolds near the sea, a robe might feature a wave pattern. Masks are also on display in the museum and it is noticeable that their styles and types did not change overtime: indeed, it is customary to emulate precisely prototypes dating from before the Edo period, in appreciation and as a mark of respect for their pure forms that transcend individuality.

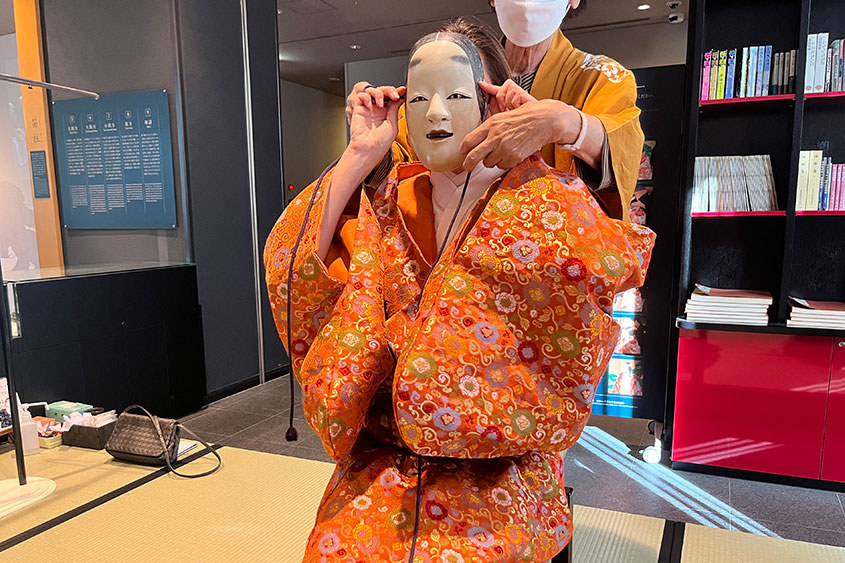

The curator invited me to enjoy a special experience offered by the museum, which is to try on a costume and a mask. Along with hearing about Noh and admiring related artefacts, this bodily experience brought an exciting new dimension to my visit. Two ladies helped me put on the robe properly and then handed me a mask, explaining that it needs to be handled with the utmost care and by placing only the tips of my thumbs and index fingers in a specific place by the rim. The mask, carved from wood, was very light and the holes for the eyes were surprisingly small. By being able to feel all this just for a few minutes, I was in awe of Noh actors who can perform while wearing a heavy costume and with their field of vision quite limited. Then the ladies from the museum encouraged me to try and strike some basic postures. In Noh, subtle movements can indicate a variety of emotions. To express happiness, I was told to slightly tilt my head up (as the mask catches more light, it appears to be smiling). I was then directed to look softly downwards, demonstrating sadness.

The archetype of Noh was created by Kan’Ami and his son Zeami in the 14th and 15th centuries. Like their followers, they were heavily influenced by Zen, its views on life and death and its aesthetics. As the museum curator explained, it is often said that “Noh is Zen with movement”. It is very fitting then that the nearby D. T. Suzuki Museum was next on my itinerary.

Kanazawa Noh Museum

- Place

- 1-2-25 Hirosaka,Kanazawa,Ishikawa 920-0962,Japan

- Time

- 10:00 a.m. ~ 6:00 p.m. (last admission at 5:30 p.m.)

- Closed

- Mondays and the year change period.(The museum may be closed at other times for changing of exhibits.)

- link

- https://www.kanazawa-noh-museum.gr.jp/english/index.html

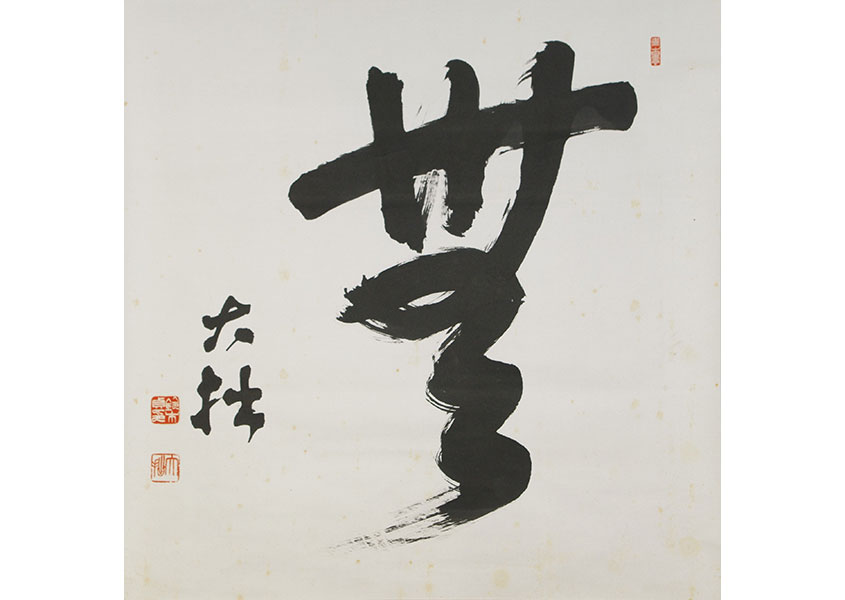

That museum is dedicated to the eminent Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki (1870-1966), who was born in Kanazawa. It is a different kind of museum, with only a very small number of art works on view. This is a place for learning, self-reflexion and contemplation, which is remarkably facilitated and enhanced by the handsome building and gardens designed by Taniguchi Yoshio. Attractive photos hint at Suzuki’s life, who travelled the world and had a key role in introducing Buddhism and Zen to the West. In another gallery, I could admire examples of calligraphy, at first for their sheer aesthetics since there are no labels. But explanations are available, in Japanese and English, and I read a few well-written leaflets that provided explanations on concepts such as mu (nothingness) and mu-shin (free mind), anecdotes about Suzuki’s life and quotes from his books.

Water Mirror Garden and Contemplative Space

D. T. Suzuki, calligraphy “Mu”

The last section of the museum was mesmerizing. It consists in a serene water garden and a square room dedicated to contemplation. Resting on a square tatami stool, I can admire the pure geometry of the Water Mirror Garden and the elegance of the materials employed by Taniguchi, including white plaster walls and a pink-hued stone. The large pool of water, also square, reflects tall trees from the surrounding forest, the sun and some passing clouds. Every about three minutes, the surface of the water is gently animated by a silent ripple forming concentric circles. The circle is a common symbol in Zen; it can have different meanings and a full, perfect shape can suggest enlightenment. On my way out, I could pick up three leaflets containing words by D. T. Suzuki and thus prolong my encounter with the Buddhist philosopher.

D. T. Suzuki Museum

- Place

- 3-4-20 Honda-machi, Kanazawa, Ishikawa 920-0964, Japan

- Time

- 9:30a.m. ー 5:00p.m. (No admittance after 4:30p.m.)

- Closed

- Mondays(If Monday is a national holiday,the museum closes on the next weekday.)

New Year's Holidays(December 29th-January 3rd)

※Closed occasionally for the replacement of exhibitions etc. - link

- https://www.kanazawa-museum.jp/daisetz/english/

To cap the day off, I was invited to have tea in a historical tea-room that has been preserved and reassembled in the centre of town, in the garden facing the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art. In another moment of awe, reflection and wonder, I walked through a small garden, entered inside and sat on tatami. I enjoyed the silence before hearing the water boiling and then my host whisking the green tea. I took in the beauty of the tea utensils as well as the wagashi, the traditional confectionary that was offered to me. The art of tea, or chanoyu, has deep spiritual and philosophical roots and is associated with Zen Buddhism: ritual tea drinking was first practiced in Japan during the Kamakura period (1192-1333) by Zen monks who drank tea to support them during their long hours of meditation.

Having drunk the tea, we discussed the concept of ichigo ichie. Literally meaning ‘one time one meeting’, it reminds us that each moment is unique and that each encounter is singular, unrepeatable. The expression has its origin in the tea ceremony, but it is also applied to the world of Noh. Indeed, I was astounded to learn that actors, even though they practice a lot by themselves, only do one single rehearsal all together.

During these experiences in Kanazawa and the discussions that accompanied them, which ranged from Zen to calligraphy and performing on stage to serving tea, I felt a unifying thread running through was the high level of concentration required in all these practices. The deliberate gestures, great application and thoughtfulness impressed me, and I felt lucky to be able to learn more about these aspects of Japanese culture and to get a glimpse into their timeless spirit.

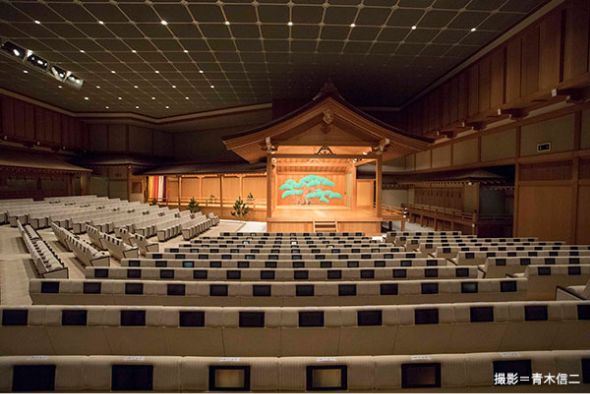

After learning about the history of Noh and admiring related artworks from up close at the museum, it is of course a special treat to be able to see a play. The National Noh Theatre in Tokyo provides a uniquely fulfilling experience: its stage floor is built with 400-year old hinoki (cypress) wood, the lighting quality is kept close to natural luminosity so that the costumes can reveal their splendour, and individual LCD screens discreetly placed on the back of each row of seats provide English subtitles and descriptions, ensuring foreign visitors can fully appreciate the performance. Plays are staged regularly throughout the year. The informative website (in English) offers online booking.