Diverse nature fostering a diverse culture

National Museum of Nature and Science

Japan Cultural Expo 2.0 pursues various projects related to Japanese traditions and Japan’s unique culture. However, Japanese people tend to take the idea of “Japaneseness” for granted and thus have few clear opportunities to explore the concept and examine how and when it arose. When considering these origins, we first need to look at Japan’s distinctive Landform, climate, flora, fauna and other environmental conditions. These form the basis of human history and they also gave rise to Japan’s unique human/nature ecosystem, lifestyle patterns, and cultural landscapes. To get a new perspective on the majestic natural history of the Japanese islands, the first port of call has to be the National Museum of Nature and Science in Ueno Park, Tokyo.

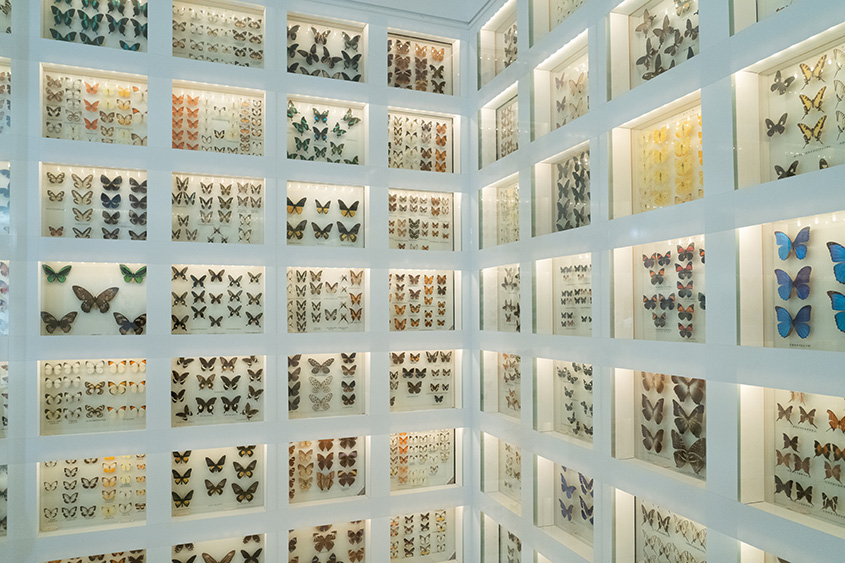

Founded in 1877, the National Museum of Nature and Science is the only national museum in Japan offering a comprehensive exhibition of natural history and science. The museum researches the evolution of the Earth and life, and the history of science and technology. Its activities cover a wide range of fields, from zoology, botany, mycology, mineralogy, paleontology, anthropology, to history of science and technology, physics and chemistry. In addition to the Global Gallery and Japan Gallery in the Ueno district, the museum comprises research departments, collection storages and a botanical garden in other districts.

The Japan Gallery is a particularly great place to explore the concept of “Japaneseness.” Its permanent exhibitions cover the nature and history of the Japanese archipelago, the evolution of its flora and fauna, the process by which the modern population was formed, and the history of the relationship between the Japanese people and nature. The Japan Gallery is also synonymous with its iconic and magisterial reconstruction of Futabasaurus suzukii, the first case in which the entire skeleton of a vertebrate fossil from Japanese Mesozoic was reconstructed.

During the Miocene epoch (23.03 million to 5.30 million years ago), the Japanese archipelago separated from continental Asia. As part of this process, the Sea of Japan expanded some 16 million years ago, with the influx of warm oceanic currents creating a humid climate. Temperature differences between the north and south of the archipelago combined with the undulating terrain formed through orogenesis (the process of mountain building) to create a land of mountains and lowlands, where monsoons led to clearly differentiated winters and summer temperatures. Over time, Japan’s climate diverged from the continental Asia and developed into one with four distinct seasons. In the periods when sea levels declined, Japanese Islands connected to the continent. This connection witnessed the immigration of flora and fauna similar to that seen in Japan today.

I was guided around the National Museum of Nature and Science by two of its researchers, Atsushi Ebihara (botany) and Megumi Saito-Kato (paleontology). On a tour like this, you realize how little you know about the plants and animals from Japan and the surrounding areas.

“Japan was recognized as one of the world’s 36 biodiversity hotspots by the environmental NGO Conservation International. A biodiversity hotspot is an area with a globally high level of biodiversity that is also threatened with destruction. Japan owes this biodiversity to its richly-varied climate and geography. The exhibits also show how Japan has a comparatively-high number of endemic species (species found nowhere else) compared to similarly-sized island nations like Great Britain and New Zealand. For example, around one third of Japan’s plants are endemic.” (Ebihara).

In 2025, visitors will be able to experience Japan’s rich biodiversity in a new program shown at Theater 36◯, an immersive full-sphere projection system in the Japan Gallery. Atsushi Ebihara and Megumi Saito-Kato are also involved in this project.

“The Japanese Peninsula was formed by techtonic movements and volcanic activity. It stretches 3000 km from south to north and has a complex climate and geomorphology ranging from subtropical Okinawa to subarctic Hokkaido. The new program introduces this rich abundance through scenes of animals and plants interacting with their habitats in rivers and river basins, but the stars of the show are amphibians like the Japanese giant salamander. It was perhaps a brave decision not to feature the mammals we all know and love, but we wanted to create a beautiful film that packs a powerful punch.” (Saito-Kato)

It may sound surprising for creatures that live in or around water, but most amphibians cannot cross the sea. Furthermore, many are only adapted to very localized environments. As such, they were chosen as symbols for the Endemism of this island nation.

And perhaps it was the diverse landform, climate, flora and fauna of the Japanese archipelago that gave rise to its richly-varied culture.

National Museum of Nature and Science

- Address

- 7-20 Ueno Park, Taito-ku, Tokyo 110-8718

- Hours

- 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (Last entry allowed until 30 minutes before closing time.)

*Opening hours are subject to change. Please check the museum's website for updates.

Closed every Monday (If Monday is a national holiday, the museum will be open on that Monday and closed the following Tuesday.)

Closed for Year-End/New Year Holiday (December 28 to January 1)

*Closing days are subject to change. Please check the museum's website for updates. - Admission

- General and university students:630yen

*Admission is free for high-school students and younger or persons aged 65 or over.

*Special exhibitions may vary, so please check the museum’s website for details.

Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

Beech trees have a high water retention capacity, with the secondary beech forest covering this mountain also functioning as a “green dam.” Terraced rice fields nourished by the blessings of abundant water unfurl across the foot of the mountain. The meadows and ponds dotted around the area are home to a variety of creatures, some of them endangered. These include the Oriental dollarbird, the ruddy kingfisher, the black-spotted frog, and the Japanese diving beetle.

Niigata Prefecture sits in the central part of Honshu island and extends over 250 km from south to north. Facing the Sea of Japan and surrounded by 2000-meter-high mountains, it subsequently has some of the heaviest snowfall in Japan. In the south lies Tokamachi, a city bisected by Shinano River, Japan’s longest river. A little further south, next to the border with Nagano Prefecture and spreading across Tsunan town, is the Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama. The word “satoyama” refers to places that comprise “an environment formed by humans working in nature” and “a human settlement that utilizes the blessings of nature in a sustainable manner.”

This is an environment where human activities and nature co-exist harmoniously, where humans and nature live together in a sustainable way. The satoyama framework formed the basis of Japanese rice production, forestry management methods, and fishing practices, with satoyama becoming the cradle that nurtured traditional Japanese culture. The Satoyama Initiative was established by Japan’s Ministry of the Environment and the United Nations University in 2010. Its mission is to inform the wider world about the satoyama model in the hope it can be of use to international policy making.

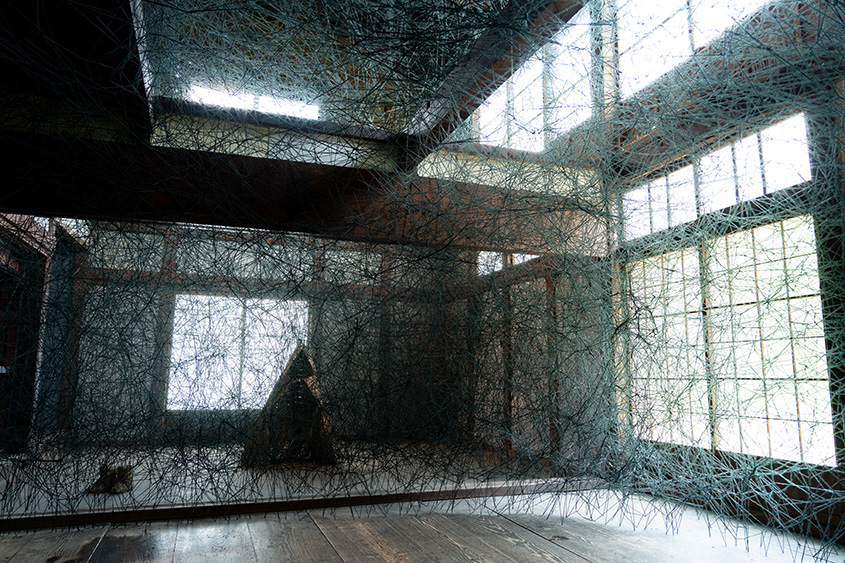

The art project Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale was launched in 2000. It is planned and run in a manner that utilizes regional characteristics by incorporating the unique scenery and history of satoyama. This pioneering Japanese art project held its 8th event in 2022. Though the Triennale is held once every three years, a special edition is also being staged from April 29 to November 5, 2023. In addition to over 200 permanent artworks, the festival features over ten special exhibitions and a number of special events. Featured works include “The Last Class,” a large-scale installation by Christian Boltanski that occupies the entire building and the gym of the former Higashikawa Elementary School; “Tunnel of Light,” a 750-meter passageway traversing Kiyotsu Gorge that has been transformed by MAD Architects, a group led by the Chinese architect Ma Yansong; and “House Memory,” an installation by Chiharu Shiota that involves filling the inside of a vacant Japanese-style house with a web of black yarn. Visitors can enjoy these works while experiencing how the satoyama landscape changes with the seasons, from rice planting to harvesting time.

This is an installation that occupies the entire building of the former Higashikawa Elementary School.

Ma Yansong and MAD Architects were invited to revitalize the Kiyotsu Gorge Tunnel, a 750-meter passageway that was opened in 1996 to provide visitors with views of the stunning Kiyotsu Gorge. The team redesigned the tunnel as a submarine and set up several new works, including lookout points along the tunnel and a Panorama Station at the end.

The artist has filled the inside of vacant Japanese-style house from floor to ceiling with a web of black yarn. Woven into the web are objects collected from local villagers that “they don’t need, but can’t throw away.”

The foundation supporting the lifestyle and culture behind these works is Echigo-Matsunoyama Museum of Natural Science “Kyororo”, which opened in 2003. The museum is energetically involved in community building and it offers education and activities to people connected to the region, from residents to tourists, with the aim of communicating the value of satoyama biodiversity, the bedrock of the region’s prosperity.

The weathered steel surface is rusty but solid. It adheres to the steel structure to form a protective coating that protects the inner section from corrosion.

“Art and science originally emerged from the same place. We hope locals consider Kyororo “their museum” and we want to provide opportunities to learn and act. Some people visit for the art festival and have no particular interest in nature, but they can also encounter the nature behind the art and learn about the beauty and mystery of nature through the filter of art. The art festival taught me about the generosity of art and how different things can be transformed into art. Museums should also refrain from teaching that there is only one correct answer or way of behaving.”

These words about the relation between art and science were spoken by Makoto Kobayashi, a curator at Kyororo who specializes in ecology with a focus on beech trees. By improving the resolution of the way we gaze at nature, we can also improve the way we view the art and culture that develops from nature. And by observing this relation between Japan’s nature and culture from the outside, perhaps we can notice things even Japanese people are sometimes unable to see.

Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

- Place

- Echigo-Tsumari region in Niigata(Tokamachi, Tsunan)

- Time

- April 29 (Sat) – November 5 (Sun), 2023

- Closed

- Closed on Tuesdays and Wednesdays except holidays