A Voyage Through a Sea of Art and Architecture

Words by Mari Hashimoto

Since the dawn of Japanese history, the Seto Inland Sea has served as an important and bustling transportation route connecting the northern part of Kyushu and the Kinai region, two of ancient Japan’s political and cultural centers. Surrounded by the islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, it is Japan’s largest inland sea and is connected to the Pacific Ocean through the Kii and Bungo Channels, and to the Sea of Japan via the Kanmon Straits. This enclosed marine ecosystem contains more than 700 islands, both habited and uninhabited, and it also borders 11 prefectures along its 7000 km-long coast, with the whole area designated as a national park because of this rich diversity.

And perhaps even more so than Tokyo or Kyoto, the region is a renowned draw for travelers with an interest in modern art and architecture.

A Japan Cultural Expo project run by the Nohgaku Performers’ Association, “Journey through Nohgaku” introduces scenic spots, temples and shrines in Setouchi (the Seto Inland Sea region) that have a deep connection with Noh theater. These include Awaji Island (Hyogo Prefecture), Japan’s first island according to myth, and Itsukushima Shrine (Hiroshima Prefecture), home to a Noh stage that seems to float in the sea. In the run up to 2025, several initiatives will also be implemented to help visitors rediscover the area’s charms through art and architecture in Setouchi and Kagawa Prefecture. One example is the Seto Art Museum Cooperation Project (Secretariat: Fukutake Foundation), which will stage fixed and touring exhibitions at Setouchi’s main art museums, principally with a focus on modern art, with a further example being exhibitions and tours that will trace the footsteps of the painter Gen’ichirō Inokuma (Secretariat: MIMOCA Foundation).

The region’s history is one of artists attracting more artists, and of artworks encouraging the creation of more artworks. Gen’ichirō Inokuma and Isamu Noguchi were among the artists who based themselves in Setouchi. Internationally active in the pre- and postwar periods, they served as a hub connecting the region to the wider world. With representative postwar Japanese architects like Kenzō Tange later designing many of Setouchi’s public buildings and art museums, the region’s cultural resources increased in depth.

This article introduces some architecture that visitors can experience in the Setouchi region, with a focus on Naoshima (Naoshima Town, Kagawa District, Kagawa Prefecture), an island with a population of around 3,000. In the 1980s, Benesse Corporation, Inc. (now Benesse Holdings, Inc.) and the Fukutake Foundation launched some cultural activities on a strip of land in the southern part of Naoshima that was originally used as a camping facility. This led on to the development of Benesse House Museum (an art museum and hotel designed by Tadao Ando) in 1992 and Benesse House Oval (a hotel also designed by Tadao Ando) in 1995. Today, all artistic activities taking place on the islands of Naoshima, Teshima and Inujima are collectively known as “Benesse Art Site Naoshima,” with countless Japanese and foreign tourists thronging to this Mecca of modern art and architecture.

After more than 30 years, these activities will reach a milestone in 2025 with the newly-announced opening of the Naoshima New Art Museum (provisional title), a museum of contemporary art designed by Tadao Ando. Though it would be impossible to describe everything the region has to offer, this article will introduce several highlights.

The adventure begins with a ferry ride from Takamatsu Port in Shikoku to Naoshima’s Miyanoura Port. The journey takes around 50 minutes and visitors disembark at Marine Station “Naoshima,” a ferry terminal designed by Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa / SANAA. This public facility was built in 2006 to serve as the new “face” of Naoshima Town. However, you would be hard-pressed to describe this as a “landmark.” Though certainly quite large, the thin, light and unobtrusive design makes the building appear to be merging into the sea and air.

This impression is reinforced by the way the grounds are mainly covered by a huge roof (approx. 70m by 52m) supported by narrow poles. Most of the area beneath is taken up by a semi-outdoor space that cars can also pass through. The interior section is made entirely of glass and its facilities include a café, a waiting room and a tourist information center. There is no clear boundary between this interior space, the port and the expansive sea beyond, with ferries, cars, passengers and architecture all melded together seamlessly. This is how every trip or stay in Naoshima begins in a smooth, frictionless manner.

Any discussion about Naoshima and architecture has to mention the architect Tadao Ando. Opened in 2013 as Ando’s 8th project in Naoshima, the ANDO MUSEUM condenses the essence of his work on the island. The museum utilizes a 100-year-old traditional wooden house, so at first glance, it is hard to believe the museum was designed by Ando, an architect associated with concrete.

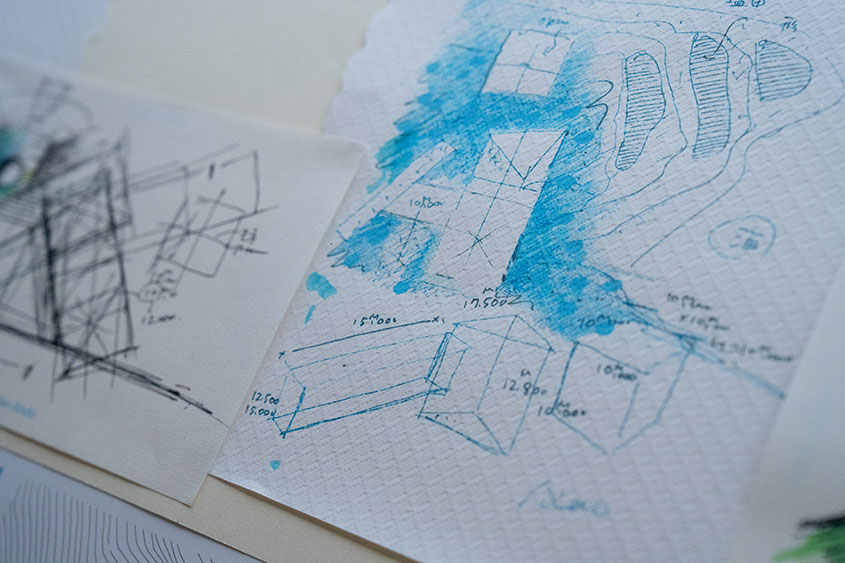

However, the impression changes when we step in the building’s interior, a space lit solely by natural light descending from a skylight opening at the top. Nestled inside here is a concrete box. Though neither a building in its own right nor a part of the furnishings or an artwork, the box captivates with its sheer sense of presence. The museum has a rich collection of sketches, blueprints and photographs, but ultimately, it’s the building itself that offers a condensed representation of an “Ando” space through its controlled usage of building materials and light.

ANDO MUSEUM

Photo:Yoshihiro Asada

2022 saw the opening of Valley Gallery, Ando’s 9th project in Naoshima, with Naoshima New Art Museum (provisional title), Ando’s 10th project, currently under construction with an eye to opening in 2025.

Benesse Art Site Naoshima began life as a “museum-like” space for staging permanent exhibitions of works by multiple artists. Over time, though, several other exhibition facilities were built, with these focusing on specific artists. One example is the Lee Ufan Museum (2010; designed by Tadao Ando). From its outdoor installations combining stones and steel plates to its semi-underground structure housing paintings and sculptures, the museum blends harmoniously with its surroundings. It’s hard to tell where the museum grounds begin, with the museum fusing with the gently undulating valley and the distant sea to form one unified piece of art. As a collaboration between Ando and the artist Lee Ufan, this bounteous space seems to fuse a feeling of openness to the wider world with a contemplation of our inner worlds.

Lee Ufan ‘Porte vers l'infini’ (2019)

Photo:Tadasu Yamamoto

Lee Ufan Museum

Photo:Tadasu Yamamoto

Lee Ufan Museum

Photo:Tadasu Yamamoto

Lee Ufan Museum

Photo:Tadasu Yamamoto

Another person wielding the twin blades of architecture and modern art to carve out new vistas is Hiroshi Sugimoto, an artist who has held a deep connection with Benesse Art Site Naoshima from the very beginning. Opened in 2022 in Benesse House Park, Hiroshi Sugimoto Gallery: Time Corridors (designed by Hiroshi Sugimoto) offers a comprehensive, in-depth exploration of Sugimoto’s worldview. The museum showcases Sugimoto’s photography, from early-period works to his latest creations. It also displays the architectural model for Go’o Shrine, which was installed on Naoshima as part of the Art House Project*. Additionally, the museum houses a lounge and furniture designed and renovated by New Material Research Laboratory, the firm Sugimoto runs with the architect Tomoyuki Sakakida. Visitors can also view sculptural works, while outside they can find Glass Tea House “Mondrian”, a work that found a permanent home in Naoshima after previous sojourns in Venice and Paris (Versailles).

Hiroshi Sugimoto Gallery: Time Corridors Lounge, 2022, Photo: Masatomo MORIYAMA

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Glass Tea House "Mondrian", 2014 (c) Hiroshi Sugimoto, Photo: Sugimoto Studio

The work originally created for LE STANZE DEL VETRO, Venice by Pentagram Stiftung

A journey from Tokyo or Osaka to Naoshima involves a series of flights and ferries, with transportation options also limited on the island itself. However, an intensely unique experience awaits visitors, one totally different from strolling around huge galleries and museums in the big cities. The art and architecture found across Naoshima and the surrounding islands are shaped by the nature, the people and the history of the Setouchi region, with a series of unforgettable encounters awaiting you there.

*Art House Project

This art project involves renovating empty houses scattered around Naoshima’s Honmura district, with artists turning the spaces themselves into works of art while weaving in the history and memories of the period when the buildings were inhabited. The project began in 1998 and it currently comprises seven locations.

Shikokumura Museum

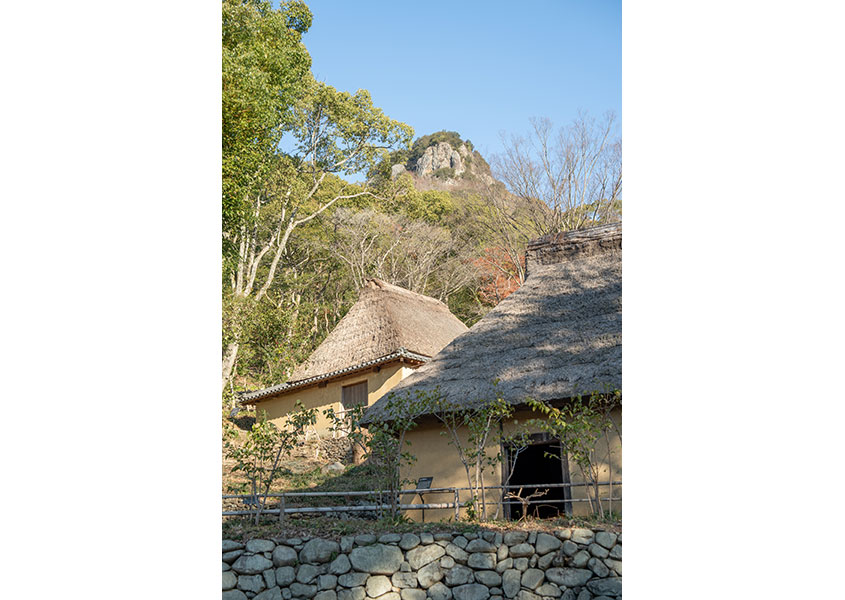

While Naoshima may be a Mecca of contemporary architecture, visitors can encounter older architecture from the Edo period (1603–1868) to the Taisho era (1912–26) at Shikokumura Museum, which uses architectural spaces and tools to introduce people to these buildings and the trades and lives conducted within them. This park lies around 20 minutes by car from Takamatsu Port in an expansive 50,000m2 site in the foothills of Mount Yashima. This area was once the setting for an ancient battle some 800 years ago, one long portrayed in works like The Tale of the Heike, the noh play Yashima, and the kabuki play Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees. The park is made up of 33 restored buildings that were relocated from Shikoku’s four prefectures. These include houses, workshops, community buildings, a theater, rice storehouses, and a soy sauce brewery, with two buildings designated as Important Cultural Properties and three as Important Tangible Folk Cultural Properties.

The first surprise awaiting visitors is the vine bridge at the entrance to the village. This is a replica of the traditional suspension bridges seen in Iya Valley, a region deep in the mountains of Tokushima Prefecture that is said to have been a secret refuge for those defeated in the fighting that shook Japan during late antiquity. The replica is made of 3.5 tons of kazura (hardy kiwi) vine and it seems quite unstable. It shakes and creaks a lot, while the large spaces between the slats make it feel you could lose your footing at any moment. As well as conjoining two physical locations, the bridge also seems to connect our world to another world beyond. After crossing the bridge, visitors are welcomed into a place where old architecture still lives and breathes.

(*There is another route available that doesn’t involve crossing the bridge. )

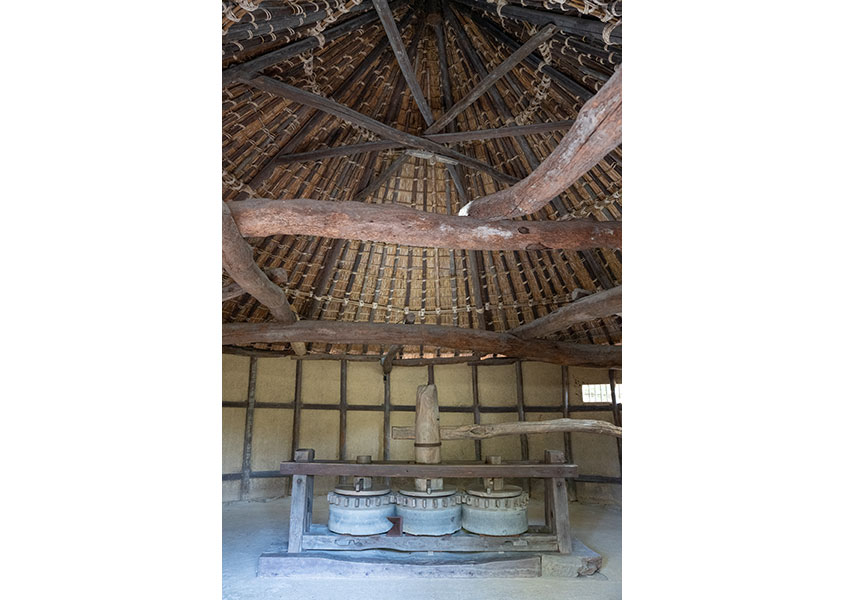

The museum also has a kabuki stage once used by villagers to perform kabuki plays themselves as part of local festivals. Underneath the stage is a revolving contraption that wouldn’t seem out of place at Tokyo’s Kabuki-za Theatre. Another building has a tapered roof like something from a Hayao Miyazaki animation. The structure used to be a hut where sugar cane was pressed using oxen. Each region in Shikoku has its own distinctive nature, climate and history, with these giving rise to distinctive architecture, art and ways of living, something these buildings vividly demonstrate.

The museum also stores 937 sugar-making implements and 5,577 implements and tanks for making soy sauce, for example. Though this collection is not on general display, curated tours are offered once a month with reservations. All these implements are valuable ethnological materials, but their forms also exude a beauty not dissimilar to art objects. In this way, the museum is making waves with its adoption of “visible storage,” a new storage trend still quite unusual in Japan.

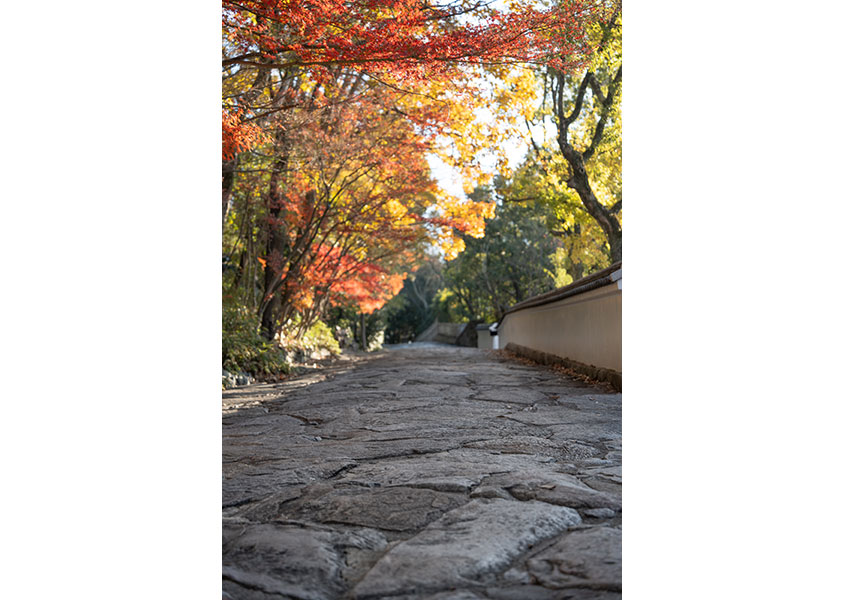

The village landscape is imbued with a sense of dynamism by the Nagare-zaka Slope. Made from flagstones of various shapes and sizes, this undulating thoroughfare connects the park’s sites. Along with the Somegataki Waterfall, it was designed by the sculptor Masayuki Nagare to form an integral part of the park. The upland area also houses the Shikokumura Gallery, designed by Tadao Ando, with the whole museum offering up a plethora of architectural and scenic highlights.

There is also plenty of architecture-themed accommodation available in the Setouchi region. Two particularly unique facilities are LOG in Onomichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, and guntû, a cruise ship that operates from Bella Vista Marina in Onomichi.

The central part of Onomichi sits in a narrow, flat plain surrounded by mountains to the north and the sea to the south. It has a very distinctive cityscape, with residential buildings, temples and shrines all crammed together on hillsides. The city is known as the “town of slopes” owing to its many steep streets and has served as a location for many live action and animation films. Halfway up one of these slopes is an apartment block built in 1963. This was designed by a team led by Bijoy Jain, founder of the Indian architecture group STUDIO MUMBAI, and was subsequently reborn as LOG.

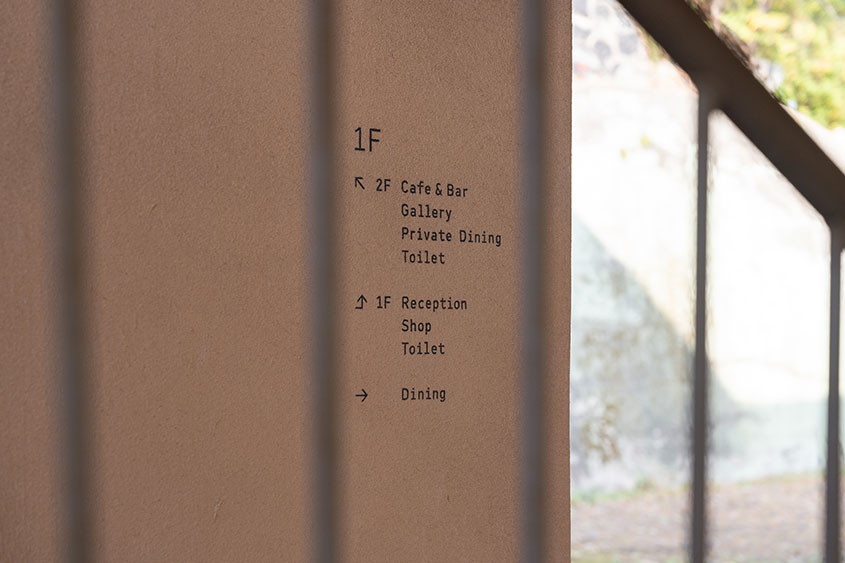

LOG has a total floor area of 1180m2 spread over three floors, with the only six guest rooms located on the third floor. An extremely large proportion of the building area is reserved for open-spaces, including dining facilities, a café & bar, a library, a gallery and a shop. Featuring a garden and plenty of open spaces, LOG was in fact originally designed as a place where guests, other tourists and local residents could freely cross paths and intermingle.

The third floor houses the guest rooms and is a private space reserved solely for staying guests. On occasion, former residents from LOG’s apartment-block days make nostalgic trips back, while the shouts of local children sometimes reverberate in the inner garden too. A record of the day’s events and photographs are sent almost daily to LOG’s designers to show them how the facility has developed and matured.

photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of LOG

photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of LOG

LOG also makes full use of old buildings and re-uses scrap materials. It sits on a hill in an area inaccessible to cars, so building materials and daily provisions have to be carried up by hand, with any waste products carried down the same way. Sustainable architecture and sustainable management have been a central part of the LOG project from the very beginning. Having recently celebrated its 5th anniversary, LOG continues to seek out modes of comfort and coziness that diverge from the path of luxurious extravagance based on squandering wealth, with LOG’s staff still passionately committed to pursuing goals they hope to achieve in the future.

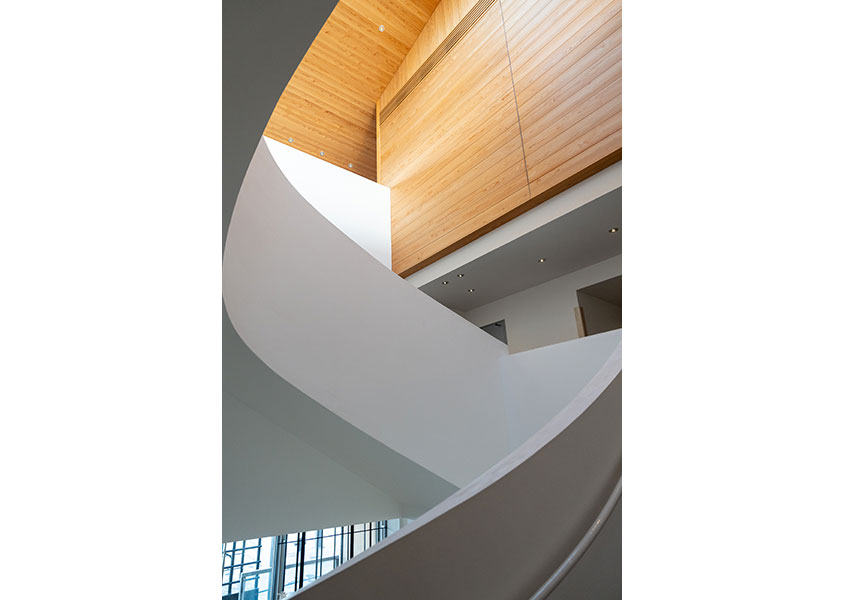

Land is not the only place where architecture has a role to play. guntû is a little cruise ship floating on the Seto Inland Sea. The ship has a gabled roof on the top and the inside are 19 cabins equipped with terraces where guests can spend their time gazing out over the sea. This is no mere luxury cruise ship, with the ship more akin to a Japanese ryokan, albeit one floating on the sea. A lot of thought has been put into the ship’s design. The interior liberally utilizes wood like sawara cypress, hinoki cypress and chestnut. Each wood has been carefully selected to match each location, while the stairwell space is coated in plaster.

©guntû

The most striking feature is the ship’s roof. The ship is almost completely covered by a huge gabled roof, so when viewed from the shore, it can appear less like a boat and more like a small floating house. Passengers can spend their time gazing out at a seascape framed by this roof and the floor. This form neatly demolishes our preconceptions of what a ship should look like. It was designed by Yasushi Horibe, a renowned designer of residential buildings.

©guntû

©guntû

From its home port in Onomichi, guntû sails west to Kaminoseki in Yamaguchi Prefecture and east to Shodoshima, an island in Kagawa Prefecture, with its routes taking in all the charms of the Seto Inland Sea. It has prepared a variety of themed cruises, with some programs exploring the Inland Sea’s scenic spots and others facilitating encounters with the islands’ local lifestyles and religious roots, for instance. While passengers are free to enjoy these activities, many choose to spend the day gazing out at the sea and islands from their cabins or the veranda in public space. This testifies to the powerful capacity of “architecture” to create spaces where activity and relaxation can coexist harmoniously.

©guntû