A rich interplay between traditional and modern Exploring Japan’s current kōgei scene

Words by Mari Hashimoto

Traditionally, sculpted objects in Japan were used for both ornamental purposes and as tools or utensils. When modern Japan encountered the West, though, a fissure emerged, with these objects now divided into artworks and decorative crafts, or “kōgei” in Japanese. Arts and crafts have long intertwined, with the two worlds converging and diverging over the eras. The 2000s have been a particularly fruitful period, with arts and kōgei crafts carving out new directions through renewed collisions, transgressions, divergences and fusions. When we look back over the history of kōgei in Japan, we tend to focus on Kyoto. To discover where it’s at nowadays, though, we need to travel to the Hokuriku region, an area facing the Japan Sea in the central part of Honshu, Japan’s main island. And at the center of this burgeoning scene is Kanazawa, a former castle town that once sat at the center of the Kaga Domain, Japan’s largest feudal estate during the Edo period (1603-1867).

It was official Kaga Domain policy to protect and nurture crafts. This rich historical context was supplemented by the establishment of art universities and research facilities for artisans. These created conditions where modern art and kōgei crafts could clash together at cutting-edge conceptual exhibitions at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa and other places, with this fertile soil also helping artists to expand their horizons and broaden their awareness of various issues. This is how the region came to be known as the “Kingdom of Kōgei.” This ascension was confirmed when the National Crafts Museum (formerly the Crafts Gallery at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) moved to Kanazawa in 2020. The same year also saw the launch of GO FOR KOGEI, a festival staged at Toyama, Ishikawa, and Fukui, three prefectures in the Hokuriku region, with the event spearheading efforts to communicate the appeal of kōgei.

In 2023, GO FOR KOGEI was staged in three areas along Fugan Canal, which runs around 5 km from the center of Toyama City to Toyama Port. The event exhibited works by 26 creators at art galleries, parks, along the canal and throughout the area’s historical streets. From crafts to contemporary art and art brut, these genre-spanning exhibits were curated by Yuji Akimoto, former Director of Chichu Art Museum in Naoshima and the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

“We didn’t use the word ‘KOGEI’ for its uniquely Japanese associations. It was more the case that ‘Art’ didn’t seem precise enough, while the word ‘Crafts’ also invites misunderstanding. We wanted to avoid strict definitions and instead choose a word that expressed the current dialogue and rapport between ‘Art’ and ‘Crafts,’ and the word we arrived at was ‘KOGEI.’”

(Yuji Akimoto)

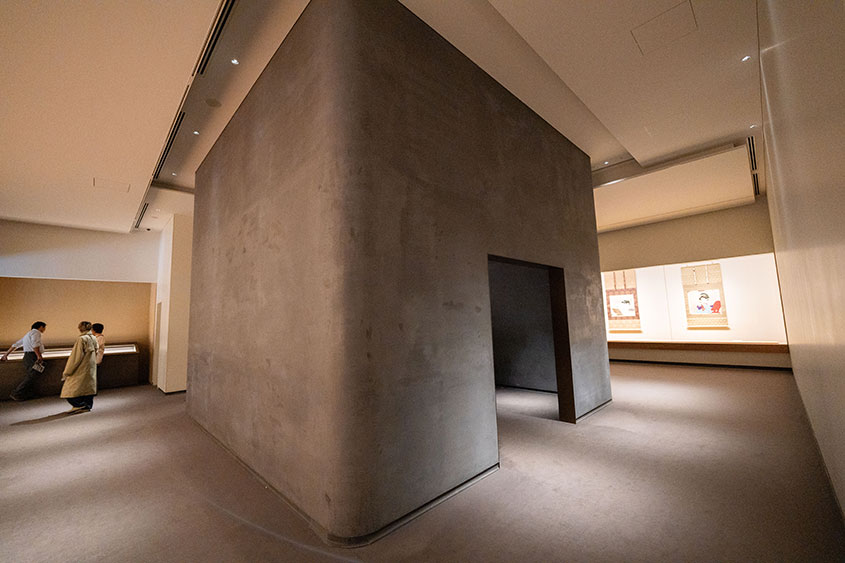

One participating venue was Rakusuitei Art Museum. Built after the Second World War, this former residence comprises a wooden two-story Japanese-style building, a reinforced concrete European-style structure, and an earthen-wall storehouse. The museum opened its doors in 2011 following work to conserve and renovate its precious buildings. The exhibits here focused on works made of clay and earthen materials, a format stretching beyond pottery to encompass a richly diverse world of expression. One installation by Takuro Kuwata featured around 3,000 malformed and unfinished works from the artist’s atelier, with these colorful ceramics blanketing the museum’s veranda. Shining within the darkness of the storehouse, meanwhile, was a work by Kim Riyoo that appeared to be a cross between a Jomon-period dogū clay figurine and a giant robot from an anime.

Another discovery awaited further down the canal in Kansui Park, where sightseeing boats set off for Toyama Port. Looming above the pond water was a huge outdoor installation by Hiroko Kubo – a pair of yamainu (Japanese wolves) like those which once roamed this region.

Kubo studied sculpture in the United States and she now creates works inspired by prehistoric art, folk art and cultural anthropology. A boat journey from here takes the visitor through Nakajima Lock. Located midway along the canal, the lock uses a two-gate Panama Canal-style system to control water levels. The Nakajima Lock Control Room was the first modern civil engineering structure to be designated as an Important Cultural Property in Japan, with this facility also serving as an exhibition space during GO FOR KOGEI.

The boat drops you off just before Toyama Port. From the Edo period (1603–1868) to the Meiji era (1868–1912), this site prospered as a port of call for the kitamaebune, the ships that carried huge volumes of goods between Hokkaido and Osaka. Visitors can still see streets lined with the magnificent former residences of shipowners and sake brewers.

There are also several storehouses offering sake tasting, with this enchanting district serving up many allures to accompany art and craft appreciation. Along the way you may come across the large blue and white doors of a brewery. Though not made of porcelain, these doors are the creation of Yuki Hayama, a ceramicist known for his intricately-painted works. Hayama copied his painting onto the aluminum doors as part of an attempt to escape the confines of the ceramic and scale up his work to an architectural level.

In this way, visitors can enjoy the sights of GO FOR KOGEI while moving around at a leisurely pace on sightseeing boats or trams, with the exhibits also serving to draw our attention to the charms of Toyama’s history and culture.

“Over these past two years, in art fairs and exhibitions across Paris, London and Venice, I have encountered many works that challenge the boundaries of art and crafts. In Japan, creators are leading a discussion about the best way to approach kōgei. At the same time, though, a spotlight is also currently being shone on ‘craftsmanship’ within a West European context. I hope an awareness of this situation can lead to a slight shift in the way we approach kōgei in Japan too.” (Yuji Akimoto)

Naohiro Niiyama runs RENEW, an event affiliated with GO FOR KOGEI. Now in its ninth year, the event is held across Fukui Prefecture in Sabae City, Echizen City, and Echizen Town. However, Niiyama approaches crafts from a totally different perspective to GO FOR KOGEI.

“Craftsmanship in this region is more concerned with industrial crafts than artistic crafts. We produce ‘products’ rather than ‘artworks.’ We steadfastly search for ways to survive while updating our offerings to meet the demands of the age,” he explains.

The area around Sabae City is hive of productive activity unparalleled in Japan, with seven craft industries (urushi lacquerware, Japanese washi paper, forged knives, tansu storage cabinets, pottery, reading glasses, and textiles) packed within a 10km radius. Until around ten years ago, these industries mainly pursued a business-to-business model. This involved producing to order from other companies, with most artisans thus having little idea where and to whom their products were sold. As the area’s population aged, industrial decline and a shrinking population seemed inevitable. Not to Niiyama, though, which is why he joined forces other young migrants to set up RENEW, an event that opens the doors of the region’s ateliers to the general public.

These ateliers include one that makes urushi lacquerware, one that refines and sells urushi lacquer, one that produces large sheets of handmade washi Japanese paper for interior use, and one jointly run by 13 knife companies. The idea is to offer hands-on experiences where visitors can observe a diverse range of production methods, chat with the artisans, and participate in workshops. This simple idea has reinvigorated the area. After experiencing the passion and skills on display in these studios, visitors often purchase craft works and share their impressions with the artisans, with these small encounters giving the workers themselves a renewed enthusiasm and a new way of viewing their work.

“The past ten years has seen the opening of 34 factory shops attached to ateliers. I like to think of this as a mini industrial revolution. Furthermore, when I came here 15 years ago, I was the only new person moving here, but the population has since increased by around 130 people. I believe the average age of our artisans is also the youngest in Japan,” explains Niiyama.

This “happening area” with its revitalized artisans is attracting lots of young owners who are arriving to set up their own unique bars, restaurants and accommodation. The next challenge for Niiyama and friends is how to turn this land with no famous tourist attractions into a hotspot of “industry tourism,” where people will come to learn about and experience kōgei in the shops and ateliers.

There is still considerable interest in Japan’s traditional kōgei too. Under Japan’s Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties, the designation “Intangible Cultural Asset” is applied to performing arts, music, crafts and other intangible assets of high historical and artistic value that have been passed down and acquired by specific individuals and groups, with particularly valuable craft techniques designated as Important Intangible Cultural Assets. Furthermore, “individuals who embody a craft technique designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Property at the highest level, or who are a master of a craft technique” are themselves designated as holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties and are popularly known as “Living National Treasures.”

Atami in Shizuoka Prefecture lies around an hour’s ride from Tokyo by bullet train. Facing the Pacific Ocean and with Mount Fuji in the background, Atami is also home to MOA Museum of Art, which houses a renowned collection of pre-modern kōgei decorative crafts, including the 17th-century National Treasure Tea-leaf Jar with a design of wisteria by Nonomura Ninsei. The museum actively promotes Living National Treasures and the conservation and dissemination of their kōgei craft techniques.

After encountering Western art following the Second World War, the pioneering ceramicist Kazuo Yagi decided to shed off considerations of utility and instead engage with nonfunctional sculptural pottery. He said the following about kōgei:

“With painting or sculpture, the concepts come first and these then determine the materials and techniques. For me it’s different, though. For me, the materials and techniques come first…My process begins purely by focusing just on the clay.”

Though Yagi’s works tend towards nonfunctional expression, it could be said that materials and techniques form the starting point for all works of Japanese kōgei. MOA’s Director Tokugo Uchida is an expert in the history of kōgei. He wants to reconstruct a way of the thinking that supports this world where “materials and techniques lead the way to expression.”

“The identification with ‘nature in itself’ is a consistent theme in Japanese culture. Unlike modern art with its clear concepts and modern kōgei with its forms of self-expression, traditional kōgei has lacked a rich vernacular to express its own identity to the outside world. Traditional kōgei crafts are often spoken of in terms of functional beauty or everyday beauty, but there is a deeper richness to the thinking behind these crafts and the expression born of this deep connection with ‘nature in itself.’ It is our job as researchers to express this richness succinctly in words that convey its value to the wider world,” he explains.

The Seven Living National Treasures exhibition was being held when I visited the museum (the exhibition finished on October 17, 2023). Works by 12 Living National Treasures had previously been introduced in HOMO FABER 12 Stone Garden: Naoto Fukasawa and 12 Living National Treasures, a 2022 exhibition curated by Uchida and held in a space arranged by designer Naoto Fukasawa. Staged on fixtures specially designed by Fukasawa for the Homo Faber Event held in Venice the same year, these striking displays presented a new image of these “traditional” craft works.

MOA also plans to hold a hands-on workshop as part of the activities of Japan Cultural Expo 2.0 (the details will be announced on MOA’s website). As a veritable treasure trove of kōgei, the MOA Museum of Art offers a wealth of unique experiences, from tea ceremonies that use high-quality utensils, including objects made by Living National Treasures, to displays where visitors can try on modern kimonos. All these experiences present a wonderful opportunity to deepen our understanding of kōgei decorative crafts.

Oni-Hagi Type Tea Bowl, by Miwa Kyūsetsu XI

Tea Bowl, with design of snow and plum blossoms in overglaze enamel, white slip and sumi-hajiki resist, by Imaizumi Imaemon XIV

Nakano Tea Bowl, with a moon-white celadon glaze, by Fukushima Zenzō

MOA Museum of Art

- Place

- 26-2 Momoyama-cho, Atami, Shizuoka 413-8511

- Access

- Buses depart from Atami railway station bus terminal: head left after you exit the station. The bus bound for MOA Museum of Art (final stop) leaves from Rank 8 and takes about 7 minutes.